Pottery displays and vault

Pottery displays and vault Pottery displays and vault

Pottery displays and vault

There is something about anthropology and archaeology museums that discourages many visitors. They are often hidden deep within the campus of a university, so visitors must make their way past dorms and bicycles and students, only to find rows and rows of dusty cabinets and a cranky caretaker. Often these museums are blocks away from parking spaces open to those without a university parking sticker.

By contrast, in Tucson, Arizona, we found an excellent, welcoming museum displaying the results of many decades of study by  Modern Native American pot

the University of Arizona. Better still, it was only a block away from a large parking garage. Housed in the beautiful old library building, the museum has several exhibit galleries.

Modern Native American pot

the University of Arizona. Better still, it was only a block away from a large parking garage. Housed in the beautiful old library building, the museum has several exhibit galleries.

One gallery is dedicated to the archaeological digs made by university students and faculty in the valley of the Little Colorado River. As it happens, we had just finished reading Song of the Lion, by Anne Hillerman, dealing with modern efforts to locate a tourist attraction at the junction of the Little Colorado and Colorado Rivers, a location of great spiritual significance to the Navajo, Hopi, Hualapai, and Havasupai tribes.

Eagle Dancers, by Pablita Velarde

Eagle Dancers, by Pablita Velarde

In the 11th to 13th centuries the conditions along the river were favorable to a more sedentary life, and a series of pueblo villages, the largest accommodating some two thousand people, were constructed on the Homol'ovi, named after the Homol, or small mesas sitting safely above the flood levels. The museum carefully explains how the results of the digs were used to determine the order in which the villages were built and later abandoned. It was interesting to learn that the abandoning of a native village was accompanied by ceremonies, to remember the ancestors that had lived there.

Wild Onion Hunt, by Solomon McCombs

Wild Onion Hunt, by Solomon McCombs

We made two trips here, because we exhausted ourselves on the first day, in which we spent several hours simply in the basketry wing, finally leaving for food without having seen the last quarter of its displays. On the second day, we returned to see the pottery collections. On both days, quite coincidentally, the campus was busy with graduation ceremonies.

Another gallery featured Native American art, along with examples of basketry over the ages. We enjoyed the woven straw objects on display (beautifully mounted in glass cases, often visible from several sides), enjoying the use of colored reeds  Modern Native American basketry

making patterns in the weaving. The people had made sandals from grasses and reeds, some of which have been preserved in the remains of early homes (the Hopi, a major group being studied, had a practice of "leaving footprints" as they migrated; they left behind things which could be replaced, or which were heavy and awkward to take with them.

Modern Native American basketry

making patterns in the weaving. The people had made sandals from grasses and reeds, some of which have been preserved in the remains of early homes (the Hopi, a major group being studied, had a practice of "leaving footprints" as they migrated; they left behind things which could be replaced, or which were heavy and awkward to take with them.

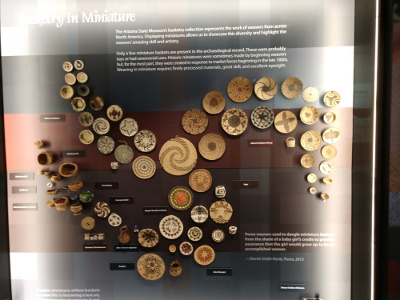

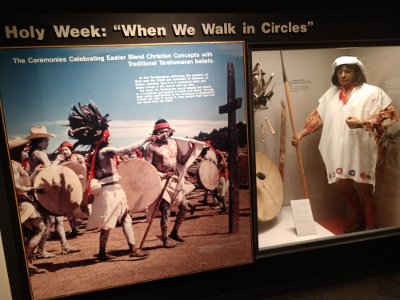

We learned a lot about the basket makers - Yaqui, Seri -- who had lived on the shores of the Sea of Cortez, between Baja California and mainland Mexico, and about the potters - including the Paiute people who had made pots now exhibited in the Lone Pine  Varying basketry styles in miniature

area of the Eastern Sierra. Some of these groups have kept themselves so separate from Anglo culture that they are mostly unknown even today. For example, a fascinating exhibit shows the Tarahumaran rituals in Spring, in which Roman Catholic Easter customs have been adopted into a ceremony involving walking in circles to provide protection against Satan. Satan is seen as God's brother, constantly at war with God, although Satan's world is not particularly horrible, unlike Hell.

Varying basketry styles in miniature

area of the Eastern Sierra. Some of these groups have kept themselves so separate from Anglo culture that they are mostly unknown even today. For example, a fascinating exhibit shows the Tarahumaran rituals in Spring, in which Roman Catholic Easter customs have been adopted into a ceremony involving walking in circles to provide protection against Satan. Satan is seen as God's brother, constantly at war with God, although Satan's world is not particularly horrible, unlike Hell.

In many cases, the Indian way of life has been threatened by invaders searching for valuable minerals or water, or other  Native Americans protecting God

resourced. Some have retreated into isolated canyons, some have attempted to co-exist. In no case have they been able to maintain their lifestyles without major difficulties. For example, the standard method for curing reeds to soften them for basketmaking is to draw them through their teeth, but industrial runoff in the local waters has caused major illness.

Native Americans protecting God

resourced. Some have retreated into isolated canyons, some have attempted to co-exist. In no case have they been able to maintain their lifestyles without major difficulties. For example, the standard method for curing reeds to soften them for basketmaking is to draw them through their teeth, but industrial runoff in the local waters has caused major illness.

We learned again of the variety of ways the dominant European culture has cheated and slain the Native Americans. One favorite approach is to command the sources of water, thereby depriving the natives of the necessity of life.

Mural by Joe Pagac

Mural by Joe Pagac

The University of Arizona continues to develop anthropologists, archaeologists and artists, so the exhibits include contemporary as well as historical materials. A major surprise to us was the understanding that the Southwest, including Northern Mexico, is rich in indigenous cultures with histories and languages that most outsiders have never heard.

There are many beautiful things to see in this city. Even before we thought of visiting the museum, we happened to turn a corner to find a splendid surrealist mural by the artist Joe Pagac, filled with creatures whose home is here.

Write us for larger copies of these pictures.